Illegal small-scale gold mining, popularly known as galamsey, remains one of the most destructive challenges facing Ghana today. Despite several interventions, the menace continues to expand, leaving in its trail poisoned rivers, degraded forests, and huge financial losses. For many experts, the time has come for ruthless and uncompromising action.

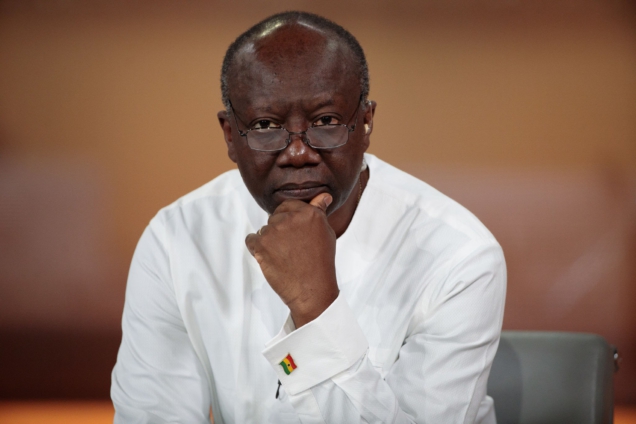

To begin with, the economic cost is staggering. The UK government has estimated that Ghana loses about US$2 billion every year through gold smuggling and unregulated mining. This is revenue that could have supported schools, hospitals, and infrastructure projects. Instead, the nation is bleeding wealth while illegal operators pocket billions without paying the required taxes.

Beyond the financial drain, the environmental devastation is even more alarming. According to the Ministry of Lands and Natural Resources, more than 5,252 hectares of land across 44 forest reserves have already been destroyed by galamsey activities. Rivers such as the Pra, Offin, Birim, and Ankobra—once lifelines for farming and fishing communities—are now heavily polluted with mercury and cyanide. Tests have shown turbidity levels above 5,000 NTU, far exceeding the permissible 500 NTU. Clearly, Ghana is losing its most vital water bodies at an alarming pace.

Moreover, the human cost cannot be ignored. Farmers are watching their cocoa farms wither due to soil degradation. Communities downstream face unsafe drinking water and rising cases of waterborne diseases. Health experts warn that long-term exposure to heavy metals could lead to irreversible health conditions. In effect, the fight against galamsey is not only about the environment but also about protecting lives and livelihoods.

In addition, public confidence in government efforts remains low. A March–April 2025 survey by Global Info Analytics revealed that 44% of Ghanaians believe there has been no improvement in the fight against galamsey since President John Mahama took office. Only 38% said the situation had improved, a clear signal that many citizens feel disillusioned with the pace and seriousness of the fight. This perception is worsened by allegations of political interference and corruption, which often shield powerful financiers behind the illegal operations.

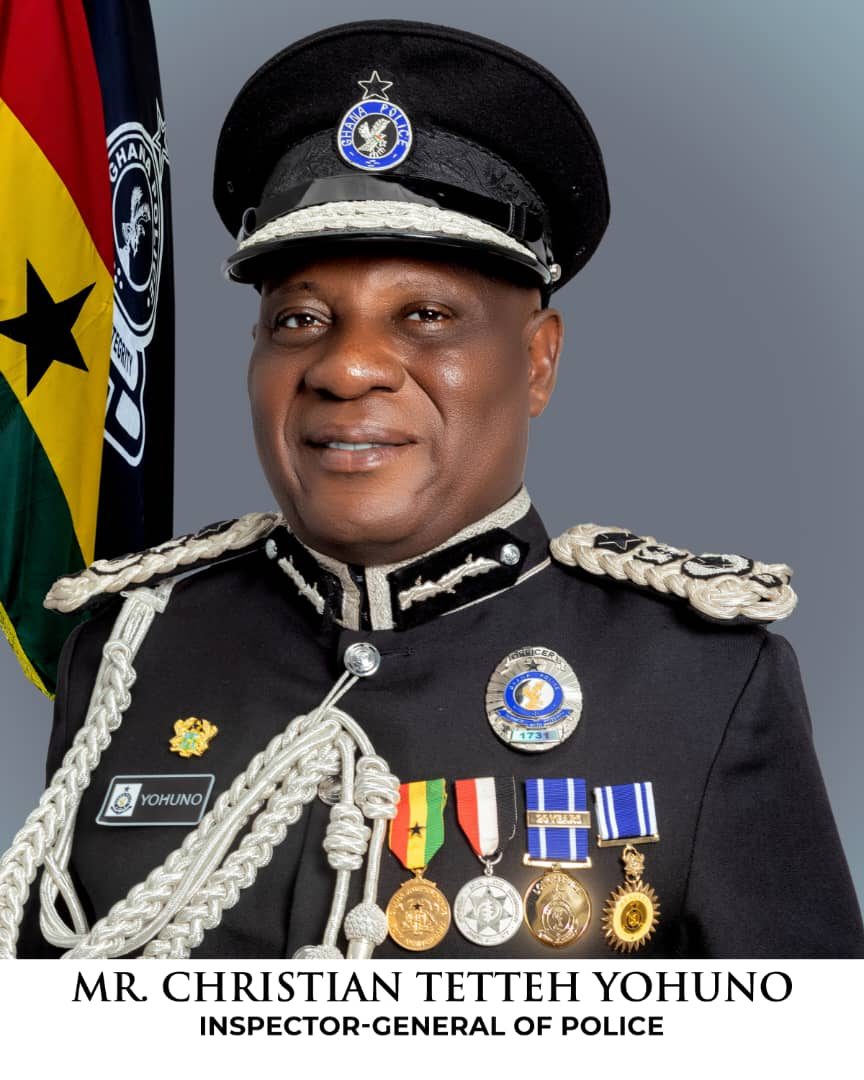

Nevertheless, the government has signaled a renewed determination. In July 2025, President Mahama inaugurated the Gold Board Task Force, a special unit made up of security agencies mandated to clamp down on illegal mining. Transitioning from rhetoric to decisive action, the task force has been empowered to arrest offenders, seize equipment, and ensure prosecutions. However, many observers insist that success will depend on transparency, accountability, and independence from political influence.

A National Emergency in Mining Areas

Given the scale of devastation, policy experts are calling for a state of environmental emergency in the worst-affected areas. Regions such as the Western Region (Amenfi Central and Prestea-Huni Valley), Ashanti Region (Amansie South and Bekwai), and Eastern Region (Fanteakwa, Atiwa, and Birim North) have become epicentres of illegal mining. Satellite images show rivers completely discoloured and farmlands stripped bare.

Declaring these zones as emergency areas would allow government to deploy additional military presence, restrict access to contaminated rivers, and fast-track reclamation projects. It would also empower the Water Resources Commission, Forestry Commission, and security agencies to act swiftly without bureaucratic delays.

Ruthless Measures Needed

To deal with this national crisis, experts argue that only bold and uncompromising measures will work.

First, the government must target financiers and political sponsors of galamsey with swift prosecutions and long jail sentences. Without cutting off the money and protection behind these operations, arrests at the site level will remain cosmetic. Naming, shaming, and convicting high-profile actors will send the strongest signal.

Second, all illegal mining equipment—especially excavators and changfan machines—should be seized and destroyed immediately at the site, as directed by existing laws. Past practices of impounding and later releasing machines have only emboldened offenders. A ruthless “no return” approach will cripple the business model of galamsey.

Third, polluted rivers and destroyed lands must be reclaimed under military-backed enforcement. Buffer zones around major water bodies should be placed under strict protection, and any encroachment should be met with rapid intervention. This would show that the state is unwilling to compromise on its ecological survival.

Galamsey may provide short-term income for some individuals, but its long-term consequences are catastrophic. Every year of delay deepens environmental scars, drains the national purse, and endangers human health. Ghana already has strong legal instruments—the Minerals and Mining Act, 2006 (Act 703) and its amendments, the Environmental Protection Agency Act, 1994 (Act 490), the Water Resources Commission Act, 1996 (Act 522), and the Forestry Commission Act, 1999 (Act 571)—all of which empower the state to regulate mining and protect natural resources. What is required now is the ruthless enforcement of these laws, without fear or favour, to safeguard the survival of the nation.

By Julius Blay JABS