Ghana’s Streets at Stake

Across Ghana’s streets, booming loudspeakers have become a daily soundtrack, often blurring the line between religious devotion and public peace.

Street preaching, also called open-air evangelism, is the practice of delivering religious messages in public spaces outside church buildings. While evangelism is a legitimate expression of faith, the unregulated amplification of sermons has raised serious concerns about noise pollution and its impact on daily life.

Historically, public preaching has long existed, but the methods were very different from what is common today. Early Christian missionaries and local evangelists often delivered sermons in town squares or community gathering spots without amplification, keeping the messages brief and respectful of the community. For example, Methodist and Presbyterian missionaries in the 19th century preached calmly in open spaces to reach those unable to attend church, emphasizing moral instruction without disturbing daily life. Pentecostal evangelists of the early 20th century sometimes held outdoor revival meetings, but these were voluntary, short, and harmonized with local life. Similarly, Islamic muezzins called the faithful to prayer using the Azan, which was structured, moderate, and designed to inform rather than dominate the neighborhood. Traditional worshippers, such as the Yewe cult among the Ewes, performed sacred songs during ceremonies that were specific, coordinated with the community, and respectful of daily routines.

Biblical examples also demonstrate that public preaching was always meant to be purposeful and respectful. John the Baptist preached repentance along the Jordan River (Matthew 3:1–6, Luke 3:3–6), drawing crowds without loudspeakers or amplification. Jesus taught in public spaces, such as hillsides and marketplaces (Matthew 5:1–2, Luke 6:17–19), using parables to guide and instruct. After Pentecost, the apostles preached in Jerusalem and surrounding towns (Acts 2:14–41), focusing on spiritual instruction and allowing people to come voluntarily. Prophets like Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel also delivered public messages, warning and guiding the people while maintaining decorum and respect (Isaiah 58, Jeremiah 7:1–11, Ezekiel 3:17–21). The emphasis in all these examples was on clarity, moral guidance, and respect for the community.

Given this context, it is necessary to clarify that this discussion is not against evangelism itself, but seeks to highlight the negative effects of excessive noise and disruptive practices from modern street preaching. Excessive amplification often exceeds 80 to 100 decibels, disturbing residents, students, patients, and workers. According to the Ghana Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), acceptable noise levels in residential areas are 55 decibels during the day and 48 decibels at night. The World Health Organization (WHO, 1999) emphasizes that continuous exposure above 70 decibels can cause hearing impairment, while the WHO (2018) Environmental Noise Guidelines for the European Region recommends that nighttime noise remain below 40 decibels, noting that levels above 55 decibels increase risks of sleep disturbance, stress, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease.

Clearly, the noise from modern street preaching far exceeds safe limits and creates both health risks and public disturbance.

Moreover, concerns extend beyond noise.

If the mission is purely evangelistic, why are offertory bowls placed before crowds, sometimes to fund instruments or electricity bills? Such practices raise questions about whether some street preaching has shifted from spiritual evangelism to disguised fundraising.

As the Bible warns, “Be careful not to practice your righteousness in front of others to be seen by them.

But when you give to the needy, do it in secret” (Matthew 6:1-4). Similarly, the Qur’an advises: “Kind words and forgiveness are better than charity followed by injury” (Surah Al-Baqarah 2:263).

Preachers are reminded to uplift without causing harm, and to ensure their worship does not disturb neighbors. Moderation is emphasized in both scriptures: “A gentle answer turns away wrath, but a harsh word stirs up anger” (Proverbs 15:1) and “…lower your voice; indeed, the harshest of sounds is the braying of donkeys” (Surah Luqman 31:19).

Accountability is equally important. Are these preachers linked to their mother churches? If so, why do umbrella bodies such as the Ghana Pentecostal and Charismatic Council (GPCC), the Christian Council of Ghana (CCG), and the Ghana Catholic Bishops’ Conference remain silent while public roadsides are turned into personal pulpits? Lack of oversight allows exploitation of both religious influence and public space.

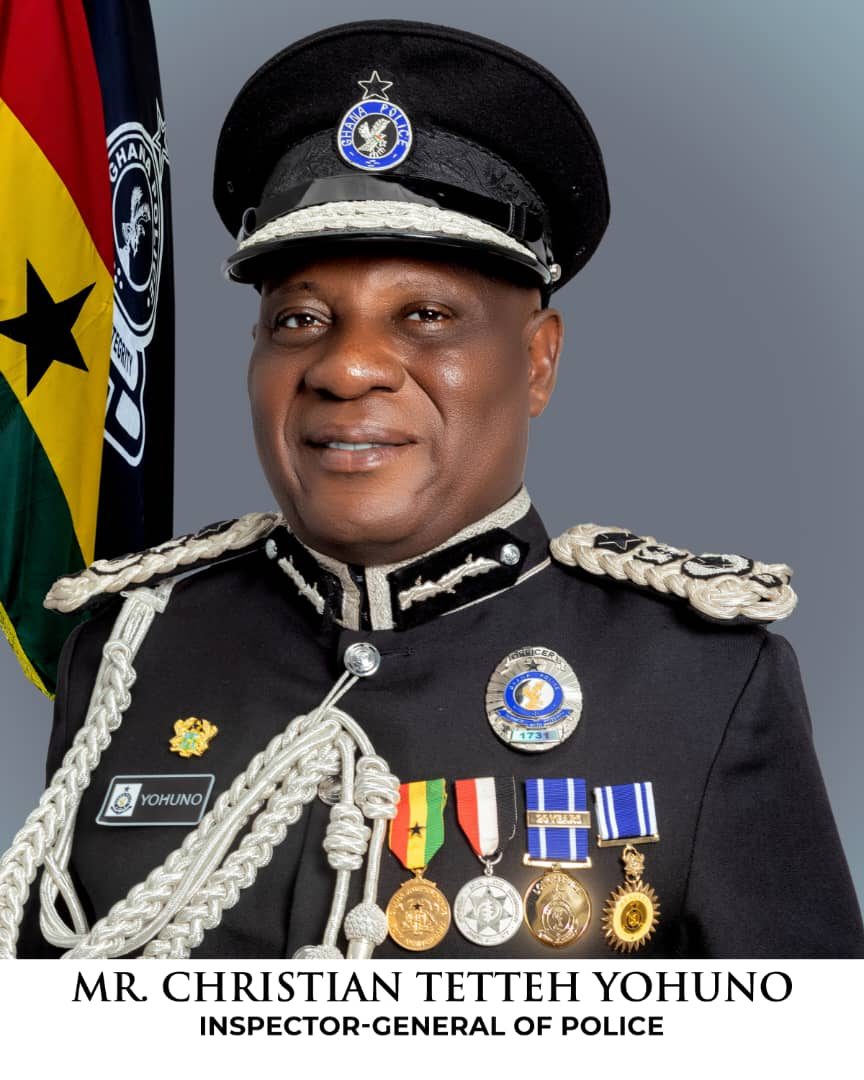

The government and regulatory authorities face a complex dilemma. Agencies such as the EPA, Municipal and District Assemblies, and the Ghana Police Service have the authority to enforce noise regulations, but many hesitate to act decisively. Politicians fear losing votes from Christian communities, civil society organizations and NGOs worry about being branded anti-Christian or “anti-Christ,” and ordinary citizens often remain silent to avoid social backlash.

This creates a situation where authorities are placed on a crossroads, balancing public health and citizens’ rights with the political, social, and religious sensitivities surrounding evangelism.

Several practical measures are necessary.

Amplified sermons in residential areas should not exceed 55 decibels during the day and 48 decibels at night, while busy streets may allow up to 65 decibels, in accordance with EPA limits and WHO guidance.

Preaching should avoid very early morning or late-night hours to prevent sleep disturbance and stress. Collection and fundraising activities should be conducted transparently and separately from sermons, ensuring that evangelism remains spiritual rather than commercial.

Umbrella church bodies must enforce accountability among preachers and regulate street evangelism to align with public interest. Government agencies must actively monitor noise levels and enforce laws to protect citizens’ health and public order.

Street preaching is a vital aspect of religious expression in Ghana, but it must be practiced responsibly. Just as the tolling church bell, the dawn Azan, and the sacred Yewe chants of old respected community life, today’s evangelism should adhere to moderation. By enforcing noise limits and promoting accountability, Ghana can protect both religious freedom and the right to peace, ensuring that the Gospel is preached without compromising public health, safety, or community well-being.

By Curtice Dumevor*