In an era where relationships are born online and nurtured across continents, human connection has become both easier and more complicated. Emotions now travel faster than borders, and intimacy often develops long before two people ever meet face to face. Within this digital reality, however, society must pause to ask an uncomfortable but necessary question: at what point does a failed romantic relationship become recast as a criminal act?

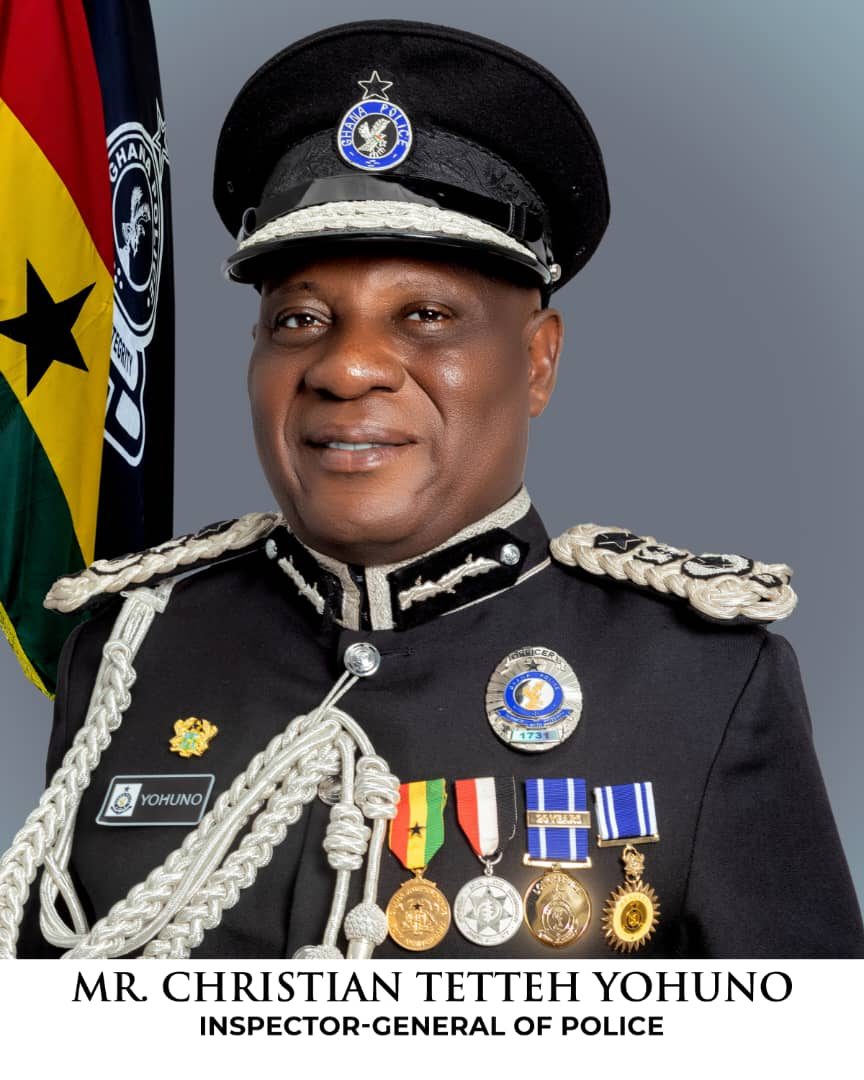

Let me state clearly from the outset that this reflection is not an endorsement of fraud, nor an attempt to excuse criminal behaviour. Rather, it is the voice of a concerned citizen thinking aloud and inviting sober reflection instead of emotional judgment. The arrest of Abutrica has once again brought to the surface a sensitive debate involving love, trust, money, disappointment, and the reach of the law.

At the centre of this conversation lies an issue that affects millions of people engaged in long-distance relationships worldwide. When affection leads to generosity and generosity later ends in regret, does the law automatically step in to assign criminal blame? Or should failed romance, painful as it may be, remain within the realm of personal responsibility rather than criminal prosecution?

One fundamental legal principle is often ignored in popular discussions. Under common law principles applicable in Ghana and many other jurisdictions, a gift remains a gift once it has been freely given. For a gift to be valid, there must be intention, delivery, and acceptance. Once these elements are present, the giver cannot later redefine that gift as fraud simply because the relationship did not end as hoped. A gift only becomes unlawful where there is clear and convincing evidence that it was obtained through deliberate deception at the very moment it was given.

In romantic relationships, particularly those conducted across borders, people regularly send money for transportation, daily upkeep, medical needs, or unforeseen emergencies. These transfers are not automatically loans, nor are they criminal acts. Unless clearly stated otherwise, they are voluntary expressions of care and support. The law does not criminalise generosity; it criminalises intentional deceit.

This distinction raises important questions that deserve careful thought. If it is alleged that emergencies were fabricated, how can such claims be conclusively proven? Is the collapse of a relationship sufficient proof that criminal intent existed from the beginning? Does the absence of receipts or formal documentation automatically mean that an emergency never occurred? Human life is unpredictable, and genuine crises rarely arrive with paperwork or official records.

Equally troubling is the possibility that emotional disappointment is being transformed into criminal accusation. When a relationship ends badly, is it fair to reinterpret voluntary acts of support as manipulation simply because feelings have changed? Should love, once freely given, be retroactively criminalised when expectations are no longer met?

Agency and personal choice must also be acknowledged. Were the funds demanded under pressure or threat, or were they freely offered out of affection and trust? Adults in relationships make conscious decisions, often driven by emotion but nonetheless voluntary. Regret after the fact should not automatically transfer responsibility to the other party.

At the heart of any fair legal assessment lies intent. When promises were made to visit, to continue a relationship, or even to marry, were those promises false at the time they were made, or did circumstances later change? Relationships evolve, and not all that fails was fraudulent from the start. Intent must be judged based on the moment the promise was made, not reconstructed through the lens of disappointment and hindsight.

Beyond the personal relationship itself lies a broader concern about cross-border justice. Why should a Ghanaian such as Abutrica be extradited to a foreign jurisdiction like the United States over matters rooted in private communication and personal relationships, especially where the alleged conduct did not physically occur on American soil? Can true fairness be guaranteed when an accused person is removed from his cultural, social, and legal environment and tried thousands of miles away?

Questions of proportionality also arise. Should international law-enforcement resources be focused on disputed romantic relationships, or should they be directed toward organised cybercrime networks that cause widespread and systematic harm? These are not emotional questions; they are policy questions that demand thoughtful answers.

This reflection does not deny that genuine fraud exists or that real victims deserve justice. However, justice loses its credibility when it blurs the line between deliberate criminal deception and the painful reality of relationships that did not survive. When the law begins to punish heartbreak rather than proven fraud, society risks criminalising human vulnerability itself.

As the world grows more interconnected, governments, lawmakers, civil-rights advocates, African freedom fighters, and international institutions must rethink how romance-related disputes are handled. The law must remain grounded in evidence, balance, and fairness. Innocent people should not lose their freedom simply because love failed.

Love involves risk. Trust requires vulnerability. Generosity sometimes ends in disappointment. These experiences are part of being human. Standing alone, they should never be enough to turn matters of the heart into matters for handcuffs and prison cells.

By Curtice Dumevor,

Public health expert and social analyst