A disturbing trend has emerged across Ghana’s public hospitals: victims of crime are being forced to pay hundreds of cedis—sometimes as much as GHC 600—to obtain police medical reports vital for criminal investigations. This practice, rooted in systemic neglect, undermines access to justice, violates human dignity, and fuels impunity.

The Vital Role of Police Medical Reports

Police medical reports are not mere paperwork; they are the backbone of criminal prosecutions involving assault, rape, domestic violence, and accidents. They objectively document injuries, establish links between alleged crimes and physical harm, and are essential for courts to determine liability. Without these reports, many cases collapse, allowing offenders to escape justice.

Access to Justice: A Fundamental Right, Not a Privilege

Charging victims, often vulnerable and impoverished, creates an insurmountable barrier to justice. It transforms a constitutional right into a privilege based on economic status, marginalizing the poor and vulnerable. Denying or delaying these reports because victims cannot pay is institutional cruelty—an indefensible breach of human dignity and equality before the law.

Systemic Impact: Eroding Trust and Enabling Impunity

When victims are priced out of justice, crimes go unreported, and perpetrators remain unpunished. This perpetuates a cycle of impunity, emboldening offenders and eroding public confidence in law enforcement and judicial institutions. The monetization of pain and suffering damages the moral authority of the state and weakens the social contract.

Funding Challenges Do Not Justify Injustice

While public hospitals face resource constraints, these cannot justify charging victims for police medical reports. The state bears the responsibility to fund essential medico-legal services through adequate budgets, insurance schemes, or statutory allocations. Justice should never be financed by the suffering of victims.

A Call for Leadership and Action

Elorm Kwami Gorni urges President Akufo-Addo, the Minister for Health, and the Minister for the Interior to intervene immediately. They must issue a clear directive abolishing all fees for police medical reports in public health facilities. This move would uphold constitutional values, restore dignity, and reinforce public trust in our justice institutions.

Conclusion: Justice Must Be Free and Accessible

Abolishing these fees is not radical; it is a moral necessity. Justice must be accessible to all, without discrimination or financial hardship. When the state demands payment for documents essential to justice, it abdicates its moral duty. Ghana must choose a path that prioritizes human dignity, fairness, and the rule of law—where justice is truly free for all.

Full report below:

When Justice Comes at a Price: Why Fees for Police Medical Reports Must Stop

Legal Researcher

Crown Legal Bureau, Accra

Table of Contents

- Introduction: 1

- The Police Medical Reports 2

- Access to Justice and Human Dignity. 3

- The Broader Cost: Impunity, Distrust, and Systemic Failure. 4

- Funding Challenges Cannot Justify Injustice. 5

- A Direct Call to the President, the Minister for Health, and the Minister for the Interior. 6

- Conclusion. 7

Justice cannot operate where poverty determines who is heard. It has become a common practice in government hospitals in Ghana for patients and victims of crime to be charged fees of Six Hundred Ghana Cedis (GHC 600) and Five Hundred Ghana Cedis (GHC 500) before medical officers sign or endorse police medical report forms. These forms, usually issued by the Ghana Police Service, are essential in criminal investigations and prosecutions involving assault, rape, defilement, domestic violence, and road accidents. Victims of violent crime are frequently faced with an unacceptable demand: pay before your injuries are documented. This is not a minor administrative issue; it is a systemic injustice that bars the very people the state is meant to protect from access to justice. When access is conditioned on payment, justice becomes a privilege rather than a right. And in a constitutional democracy, that is indefensible.

Police medical reports are not optional paperwork. They are the evidentiary backbone of criminal investigations involving assault, domestic violence, rape, defilement, and other forms of physical abuse. Without them, police investigations collapse, prosecutions fail, and offenders escape accountability. In Ghana, a police medical report is an official medico-legal document issued by a qualified medical practitioner at the request of the Ghana Police Service for the purpose of investigating, substantiating, and prosecuting criminal offences involving bodily harm.It records, in professional and evidential terms, the nature, extent, cause, and probable time of injuries sustained by a victim or suspect, and establishes the medical link between the alleged criminal act and the physical harm suffered.

In practical and legal terms, a police medical report in Ghana serves as:

- Primary Evidentiary Proof of Injury; It provides objective medical confirmation that an injury exists, its severity, and whether it is consistent with the alleged offence.

- A Legal Bridge Between Crime and Prosecution;The report connects the victim’s complaint to prosecutable facts, enabling the police and the courts to move from allegation to accountability.

- A Mandatory Investigative Requirement; In offences such as assault, rape, defilement, domestic violence, and other forms of physical abuse, a police medical report is often indispensable for charging and sustaining a criminal case.

- An Expert Opinion for the Courts; Prepared by a medical professional, it constitutes expert evidence that assists the court in determining liability, severity of harm, and appropriate sanctions.

- A Safeguard Against Impunity: Without it, many criminal cases collapse for lack of corroborative evidence, allowing offenders to evade justice.

For these reasons, the police medical report in Ghana is rightly described as a lifeline for criminal accountability. It is not a private medical service rendered at the convenience of an individual; it is a state-required instrument of justice, fundamental to the protection of victims’ rights and the effective functioning of the criminal justice system.To deny or delay this document because a victim cannot pay is to sabotage the justice process at its foundation. It converts a legal requirement into a financial obstacle and the state becomes complicit in its own failure to prosecute crime.

Let us be unequivocally honest: demanding payment from a battered woman, a violated child, or an assaulted citizen before their injuries are documented is not a matter of administrative efficiency. It is institutional cruelty, plain and indefensible.

For many victims particularly those in poor, vulnerable, or rural communities the required fee, however modest it may appear, becomes an insurmountable barrier. At that point, justice ends. Victims retreat. Complaints are withdrawn. Cases collapse before they begin. Silence takes the place of accountability, and perpetrators absorb a dangerous message: poverty is a shield against prosecution.

Access to justice is not a privilege granted at the discretion of the state; it is a constitutional right. Any practice that conditions the enforcement of rights on one’s ability to pay is inherently discriminatory. It punishes individuals for their economic status and converts public institutions into gatekeepers of exclusion rather than protectors of rights. Such a practice violates the very foundations of constitutional governance human dignity, equality before the law, and equal protection. Justice that is delayed or denied because of cost is not an accident of administration; it is justice denied by design.

D. The Broader Cost: Impunity, Distrust, and Systemic Failure

The harm caused by charging for police medical reports does not end with the individual victim. Its consequences ripple outward, quietly undermining the foundations of the criminal justice system and the social contract between the state and its citizens. When victims are unable or unwilling to pay, crimes go unreported or unpursued. Assaults, sexual violence, and other serious offences are buried not because they did not occur, but because the cost of proof is too high. In this environment, impunity thrives. Perpetrators remain at large, emboldened by the knowledge that the justice system can be defeated not by innocence, but by poverty.

As victims encounter financial barriers at the very first point of contact with the system, faith in justice institutions steadily erodes. Communities begin to disengage, viewing the police, hospitals, and courts not as protectors, but as inaccessible or indifferent. This loss of confidence discourages cooperation with law enforcement and weakens collective efforts to prevent and respond to crime.

Even more troubling is the message conveyed when public institutions appear to profit from suffering. The monetization of pain corrodes public trust and diminishes the moral authority of the state. Citizens begin to question whether justice is administered in the public interest or sold to the highest bidder.

The ultimate outcome is a fragile and ineffective criminal justice system one that fails not because the law is weak or inadequate, but because access to justice has been deliberately priced beyond the reach of those who need it most. In such a system, accountability becomes selective, protection becomes conditional, and justice itself loses its meaning.

E. Funding Challenges Cannot Justify Injustice

It is acknowledged that public hospitals across the country face persistent resource constraints. Healthcare professionals work under immense pressure and deserve adequate support, fair compensation, and proper working conditions. These challenges are real and must be addressed. However, none of these realities can ever justify transferring the cost of state failure onto victims of crime.

Charging victims for police medical reports is not a solution to underfunding; it is an injustice disguised as cost recovery. It places an unfair and morally indefensible burden on individuals who are already suffering physical, emotional, and psychological harm. The state cannot, in good conscience, demand payment from those it has a duty to protect. No victim should have to choose between food and justice.

The answer lies in sound public policy, not in punishing the vulnerable. Proper budgetary allocations must be made to cover medico-legal services required for criminal investigations. In addition, national health insurance policies must be expressly expanded to cover police medical examinations and reports as essential public health and justice-related services. Where necessary, government reimbursement schemes or clear statutory funding arrangements should be established to ensure hospitals are compensated without passing costs onto victims.

Victims of crime must never be turned into a stop-gap funding mechanism for institutional shortcomings. Justice cannot be financed by suffering. A system that does so abandons its moral authority and undermines the very purpose for which public institutions exist.

F. A Direct Call to the President, the Minister for Health, and the Minister for the Interior

This is a defining moment one that calls for principled, coordinated, and decisive leadership at the highest levels of state authority.

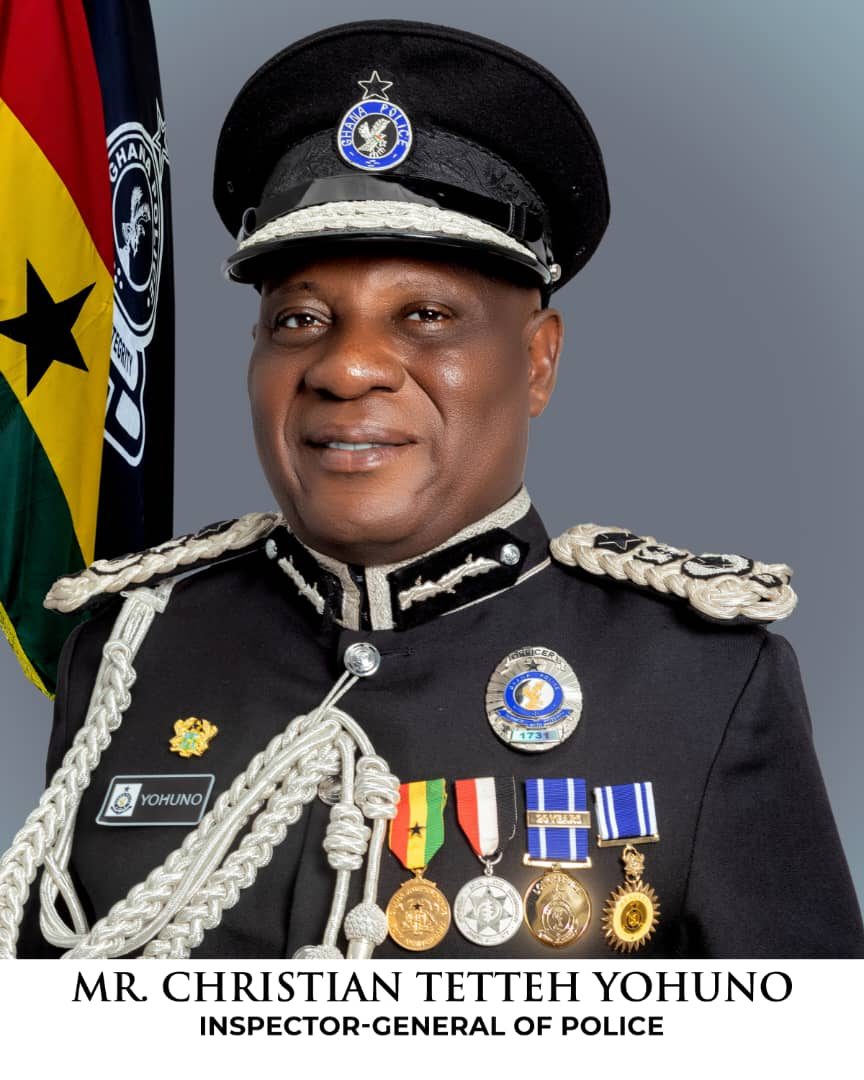

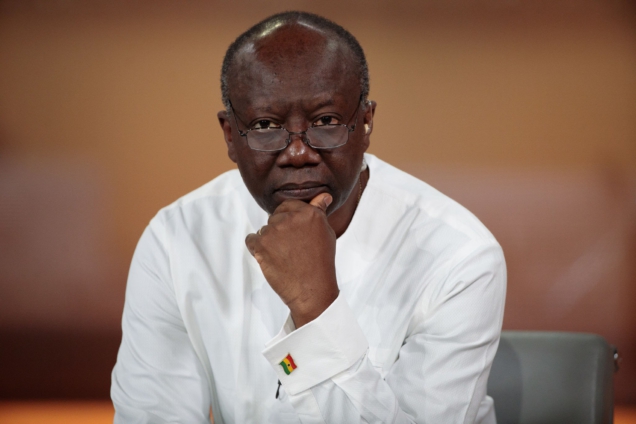

We respectfully, yet firmly, call on the President of the Republic of Ghana, as the custodian of the Constitution and guarantor of fundamental rights; the Minister for Health, as the steward of the nation’s public healthcare system; and the Minister for the Interior, under whose authority the Ghana Police Service operates, to intervene without delay. The continued charging of fees for police medical reports in public health facilities is inconsistent with constitutional values, human dignity, and the state’s obligation to ensure equal access to justice.

A clear, nationwide policy directive must be jointly issued abolishing all fees associated with police medical reports in public hospitals and clinics. This directive must be supported by adequate funding, clear implementation guidelines, effective enforcement mechanisms, and accountability structures to ensure uniform compliance across the country by health facilities and law enforcement agencies alike. Such an intervention would do more than correct an administrative irregularity. It would restore dignity to victims of crime, reaffirm public confidence in state institutions, and strengthen the integrity and effectiveness of the criminal justice system.

A police medical report is not a private or discretionary medical service. It is a document required by the state for the purposes of investigation, prosecution, and the administration of justice. Where the state mandates a document, the state must bear its cost. Anything short of this amounts to an abdication of responsibility. The burden of criminal investigation cannot, and must not, be shifted onto victims of crime. Justice is a public good, and its costs must be borne publicly if it is to remain credible, humane, and accessible to all.

G. Conclusion

This reform is not radical. It is reasonable, humane, and long overdue. Abolishing fees for police medical reports is a necessary step toward aligning practice with constitutional values and restoring fairness to the criminal justice system.

Justice must never be transactional. It must not be rationed by income, negotiated through payment, or denied because a victim cannot afford the cost of proving harm. The state cannot demand fees for the very processes it requires to fulfill its duty to protect citizens and uphold the rule of law.

This principle is already clearly recognised within the justice system itself. In the courts of Ghana, criminal cases attract no filing fees. The state bears the cost because criminal justice is a public function carried out in the collective interest of society. It would therefore be illogical and unjust for victims to be charged at the investigative stage for documents required to initiate or sustain the very criminal process that the courts have rightly made free.

When a price is placed on justice, rights are reduced to privileges and human suffering is converted into revenue. That is a path no democratic society should accept. Ghana must choose a different course one that places human dignity above administrative convenience and constitutional obligation above cost recovery.

Justice must be accessible to all, without discrimination.

Justice must be compassionate to the vulnerable, and justice must be free because anything less is not justice at all.