The indictment is clear, and it comes from the highest office: “God has blessed Ghana, but our character has denied us the full benefit. From south to north, and east to west, there is gold everywhere, so why should poverty exist in Ghana?”

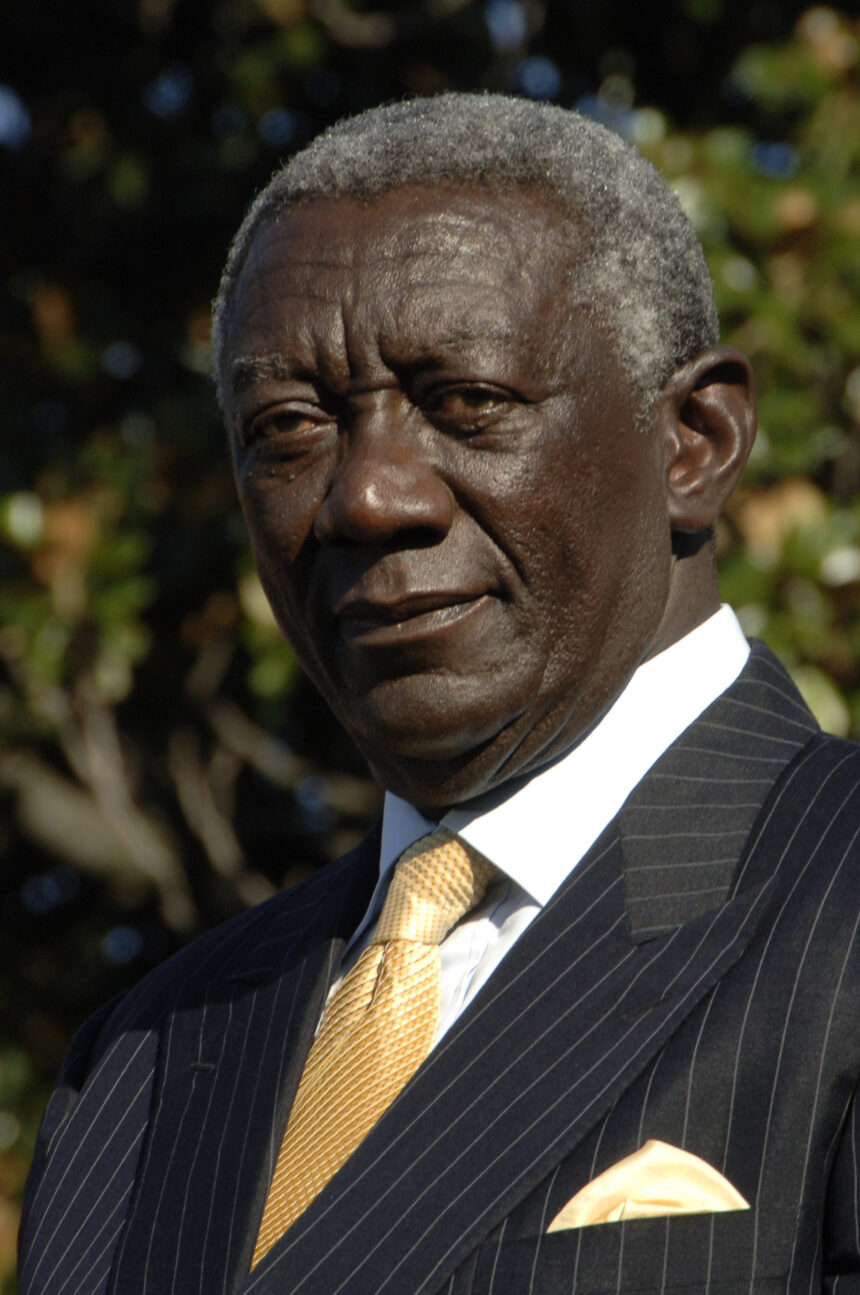

This defining observation by former President Kufuor is not merely a critique; it is a profound national diagnosis. It reveals the tragic paradox of our republic: a nation drowning in riches yet starved by the poverty of its own soul.

Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah saw this curse long before independence. He sought to inoculate us against it with the Young Pioneer concept, a deliberate engine to orient the Ghanaian citizen.

The vision was pure: to nurture a new self-confident, hardworking, patriotic citizen of unassailable integrity, committed to the collective interest above all else. Its premature death, championed by detractors with “evil intentions,” was perhaps the single greatest forfeiture of our national potential. Had that culture of character been consistently championed, the very idea of assisting foreigners to dismantle our country would be anathema, not a daily practice.

Decades later, the wisdom in that lost concept resurfaced as the National Orientation Programme. But there is a colossal difference between Orientation and Re-Orientation, and the latter is a far more arduous task.

We were already struggling with inherent human flaws, but colonialism delivered a profound negative re-orientation. It alienated us from our environment and culture, instilling a deep, debilitating inferiority complex and a parasitic dependency.

This spiritual wound is why we suffer a terminal lack of self-esteem, perpetually seeking validation from external sources. We desire to ‘belong,’ to ‘show off,’ believing material acquisition is the measure of worth.

This is the root of our endemic theft: the highly-schooled elite and the unschooled sakawa boy are united in the vanity of their corruption.

Both steal to acquire mansions and luxury cars, hosting extravagant parties, the ultimate public spectacle to manufacture importance. Men of high self-esteem build people; our men of means build only monuments to their own insecurity.

Furthermore, we are a people of least resistance, demonstrating chronic indiscipline in our roads, markets, and offices. Patience is a foreign concept; everyone seeks the shortest, most disorderly path to their destination.

This disregard for queues, rules, and order is the daily manifestation of a failed national character.

Therefore, the delusion that Ghana’s salvation lies in the cyclical change of political parties and partisan colors must end.

What we urgently need is radical, comprehensive National Re-Orientation to birth a New Ghanaian—one capable of animating our collective dreams into tangible reality.

This character transformation should have been the singular preoccupation of leadership, including the administration led by the very man who articulated the problem.

The question remains: If this truth was known long before ascending to the presidency, how did that profound knowledge fail to influence your tenure?

Why was the machinery of state often geared towards kickbacks, procurement contracts, and individual enrichment, even at Ghana’s expense?

When brown envelopes were presented, you told us you pinched yourself and asked the corrupt to return “tomorrow.” But the nation asks, what did you do when they came tomorrow?

Under your watch, Ghana Airways perished, not due to a lack of prayer sessions led by foreign clergy, but due to managerial chaos and character failure. The tragedy of the MV Benjamin 77 Parcels of Cocaine case, and the immunity granted to officials involved in ethical and financial misconduct, only served to normalize the very character flaws you diagnosed.

This is the cycle. We all fail Ghana when we fail to see that we ourselves are the character requiring change.

The solution is not a political slogan, but a Nation Character Changing Leadership, one that actively deploys Human Change Management tools to facilitate deep attitudinal and behavioral shifts.

How, for instance, can we change the transactional, shortcut-seeking kalabule trader without a structured, persistent commitment to re-orientation above the fray of multi-party politicking?

The character deficit is our constitutional crisis. It is time for leaders to stop merely identifying the poison and start administering the cure.

By Raymond Ablorh