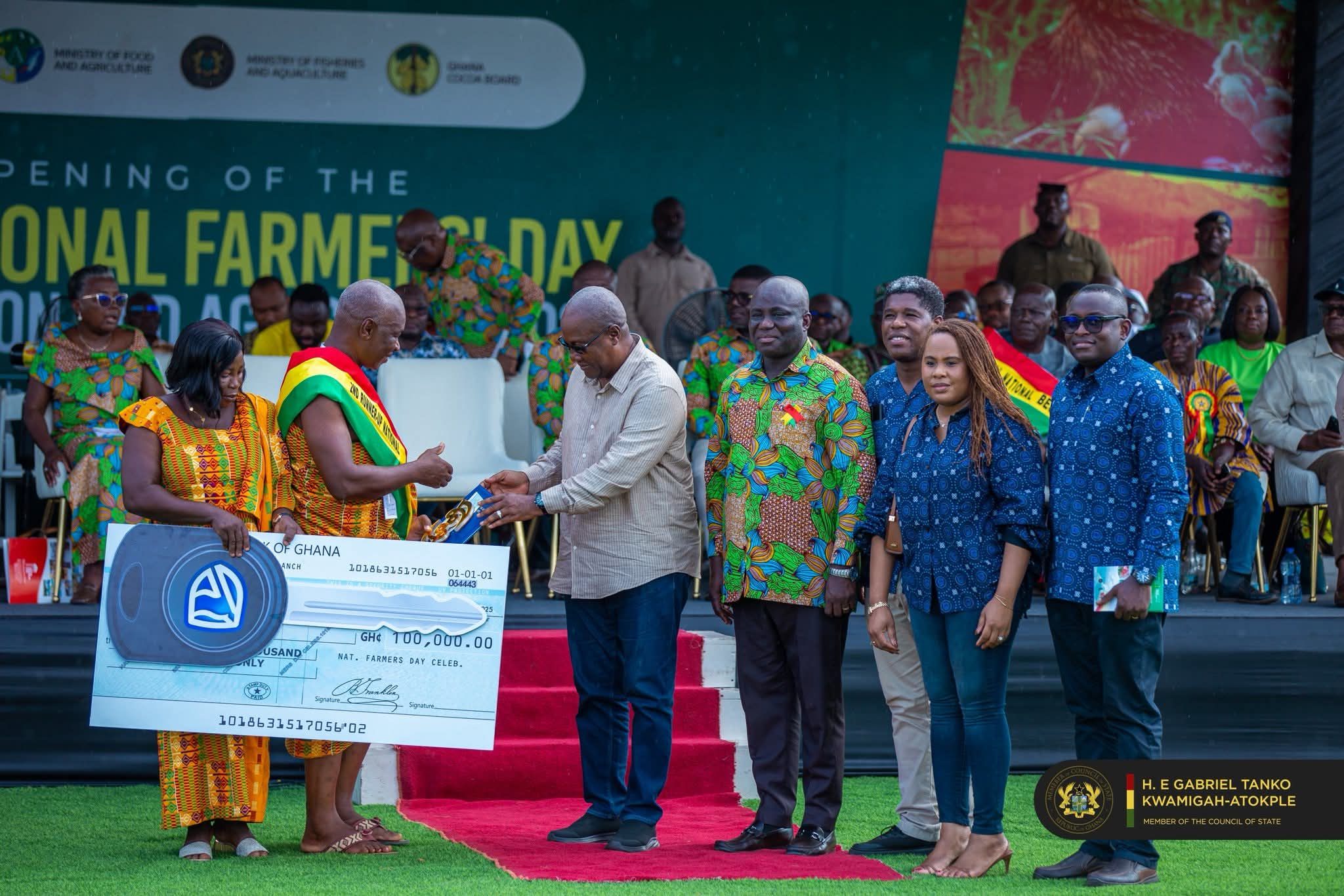

Every year, on the first Friday of December, Ghana pauses to honour the men and women whose tireless work feeds the nation, the farmers and fishers who form the backbone of the country’s economy. This year, the national celebration was held in Ho in the Volta Region, while sub-national events took place across all districts, offering mouth-watering prizes and awards to exemplary farmers, fishers, and women in agriculture.

The spectacle of celebration, recognition, and reward is inspiring, yet it compels us to ask critical questions. With all the investments, accolades, and fanfare, is Ghana truly reaping the benefits of these celebrations? Is the National Farmers Day serving its intended purpose, or has it become more ceremonial than transformational? Are we celebrating effort without ensuring lasting impact on the lives of farmers and the nation’s food security?

Instituted in 1985 by the Provisional National Defence Council government following devastating droughts and bushfires, National Farmers Day was meant to recognize resilience, promote modern agricultural practices, inspire youth participation, strengthen food security, and foster collaboration between farmers and policymakers.

It is designed to honour excellence while encouraging innovation, mechanization, and sustainability. Yet, despite decades of celebration, can we confidently say that Ghana has achieved food security? Are our farms producing enough to feed the nation year-round, or do we still rely heavily on imports for staples? Even if food is available, what about nutrition security? Are Ghanaians eating well-balanced, nutrient-rich diets, or is hunger hidden in the plates of many households?

Over the years, the celebration has yielded some gains. Farmers and fishers have been motivated through awards, crop production in maize, rice, yam, cassava, cocoa, and vegetables has improved, fisheries and aquaculture have expanded, and youth and women’s involvement in agriculture has gradually increased.

Policy initiatives like Planting for Food and Jobs, Planting for Export and Rural Development, fertilizer subsidies, and mechanization support were influenced by the spirit of recognition and reward. However, how much of this translates to long-term transformation? Are these programmes sufficient to overcome the persistent challenges of erratic rainfall, climate change, poor irrigation, inadequate financing, high post-harvest losses, expensive inputs, and land tenure disputes?

Are we investing enough in storage, processing, and market linkages to avert post-harvest losses that continue to plague farmers year after year?

Recent reports in the media highlight devastating losses suffered by farmers across the country. Take, for example, the tomato farmers in Anloga, whose produce rotted due to lack of storage facilities and poor market access, or cassava, maize, and yam farmers in other regions who have experienced similar misfortunes.

These losses raise difficult questions. How can we expect the youth to embrace agriculture as a profitable and respectable career when their efforts may rot in the field or be sold at a loss? If the government truly values youth participation in agriculture, why are critical support systems such as storage, processing, and transportation still inadequate? How do lavish celebrations and prizes reconcile with the harsh realities that ordinary farmers face every harvest season?

Another pressing issue is the decline in the posting of Agricultural Extension Officers, especially graduates from agricultural colleges, who are trained to support farmers with knowledge, innovation, and modern techniques. Why is the government no longer posting extension workers as before, leaving graduates idle in their homes? Take the case of Mr Christopher Tetteh, who completed Agricultural College in Ohawu almost five to six years ago and is still unemployed despite his qualification.

How can the government justify spending lavishly on celebration and awards when trained personnel who could directly assist farmers remain unused? Does this not reflect a misalignment between policy intent and practical implementation?

Even as Ho hosted the national event with grandeur and districts distributed awards and incentives, these questions linger. Are Ghana’s farmers truly supported to increase productivity and income? Are we investing in infrastructure, market access, and youth empowerment as much as we invest in ceremonial fanfare? Are these celebrations translating into systemic change, or are they mere photo opportunities and public relations exercises?

Are the millions spent each year producing tangible outcomes in the fields, or are they mostly symbolic?

National Farmers Day is a celebration of resilience, dedication, and national pride, but it should also be a mirror reflecting the realities of Ghana’s agricultural sector. While we cheer, applaud, and honour the hands that feed the nation, we must also confront uncomfortable truths. When will these celebrations translate into real progress?

When will Ghana become a food-secure nation not only in quantity but also in quality, nutrition, and sustainability? Are policymakers prepared to confront structural challenges, prioritize extension services, empower youth and women, and ensure that the investments into agriculture beyond ceremonies produce lasting results?

National Farmers Day remains a symbol of hope and unity, but it is also a call to action. It is a reminder that honouring our farmers is meaningless unless it results in measurable food security, improved livelihoods, and a sustainable agricultural sector that can confidently feed Ghana today and for generations to come.

If the nation truly values agriculture, it must answer these questions, act decisively, and ensure that celebrations of farmers are matched by genuine policies, infrastructure, and support that transform agriculture from mere tradition into a thriving, sustainable, and profitable sector.

By Curtice Dumevor – Public health expert and social analyst