The quill of Mat Whatley, dipped not in ink but in the residual brine of empire, has produced a polemic less about Ghana and more about the ghosts that still haunt the British psyche.

He sees in a sovereign nation’s pragmatic policy an echo of an old enemy, mistaking the discipline of survival for the sin of socialism. This is the ultimate paradox of the imperial mind: it demands the world conform to its own narrow ideological spectrum, and anything outside that light is cast into a convenient darkness.

Whatley frames a contractual adjustment on a debt, a mundane, multilateral mechanism, as the high drama of London tossing coins from a gilded balcony.

This is not journalism; it is a hyperbole of hubris. He seeks to clothe a basic trade facilitation agreement, consistent with the very frameworks the UK itself helped forge, in the shimmering raiment of charity. To suggest the extension of a loan repayment by 15 years, a move that unlocks UK Export Finance (UKEF)-backed infrastructure projects, is an act of benevolent gift-giving is to fundamentally misunderstand the architecture of global finance. “When the rich man pays his dues late, it is a business decision; when the poor man does, it is a moral failure.”

His logic is as brittle as old parchment: Britain’s economy trembles, and it is a technical correction; Ghana’s economy adjusts, and it is a moral plea. This is the ultimate metaphor for the power dynamic he seeks to preserve, where the multilateral table of equals shrinks back into a pedestal for the former master. The debt restructuring is not a handout; it is the cutting of a vine whose growth was mutually agreed upon.

Whatley’s attempt to weaponize the educational past of a Ghanaian president is an allegory of intellectual myopia. If studying in Moscow three decades ago permanently affixes the label “Soviet sympathiser,” then by the same absurd calculus, every student who ever walked the polished stones of Oxford must pledge fealty to a crown that still benefits from centuries of systemic injustice. Ghana’s foreign policy is not a banner of rigid ideology; it is the sail of a small boat navigating a tempestuous geopolitical sea. He laments ‘defiance,’ but the only defiance is against the expectation that a Black nation’s choices must still be validated by a Western capital. It is the wisdom of the proverb: “The toad does not run in the daytime for nothing.” Ghana’s neutrality is the hard-won skill of survival, the necessity of trading with the North, South, East, and West alike, while the cowboys of the West lecture about democracy while Gaza bleeds, a juxtaposition that should shame any self-proclaimed moral arbiter.

The commentary’s feigned heartbreak over the judiciary is the sanctimonious dirge of one who mistakes his own ignorance for a constitutional crisis. The removal of the former Chief Justice, Gertrude Torkornoo, was not a dark-of-night dismissal via a “secret petition,” but the lawful, transparent, and constitutionally mandated process under Article 146. It involved the full panoply of the state: the President, the Council of State, and a duly constituted investigative committee. The law is the law is the law.

To claim this process is “lawfare” is to deploy the oldest trick in the imperial playbook: weaponising suspicion to weaken sovereignty. They seek to paint Ghana as a house of cards where justice is political, yet they remain deafeningly silent on the eight years of corruption, arrogance, and economic vandalism that preceded this moment. Silence then; outrage now. This is not a balanced view; it is a staged performance, a choreography of convenience.

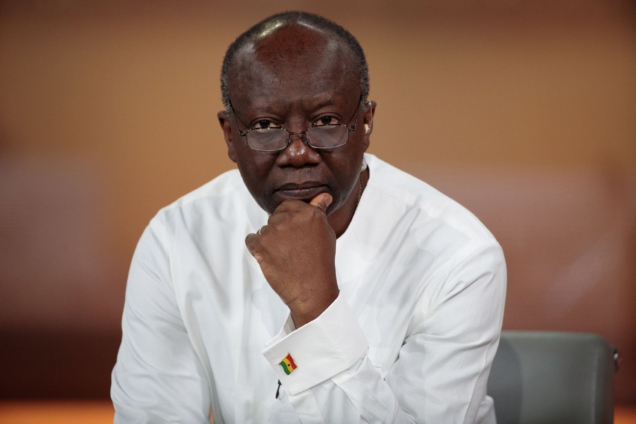

Whatley’s tearful defence of Ken Ofori-Atta, the former finance minister, is the most jarring note in his symphony of selective outrage. He casts him as a saintly reformer, yet Ghana remembers the man under whose stewardship public debt tripled, banks collapsed like dominoes, and the nation was driven, humiliated, to the gates of the IMF for a bailout. “To call the legal investigation into a man who traded Eurobonds like family heirlooms persecution is to insult the intelligence of every Ghanaian who queued for bread.”

The issuance of an INTERPOL Red Notice and a provisional arrest request are not the whimsical fictions of political vendetta; they are verifiable filings in the cold language of international law enforcement. To ignore this, while simultaneously demanding an adherence to the “rule of law,” is a paradoxical hypocrisy, a rhetorical sleight of hand designed to excuse recklessness as Western persecution.

What rented voices like Whatley fail to grasp is the essence of sovereign democracy: Ghana is a nation rediscovering its moral compass, not a “bad port of call.” His article is not a critique; it is a colonial tantrum, a whisper from a faded era that still expects applause for mispronouncing the truth.

As Chinua Achebe warned, “our own men and our sons have joined the ranks of the stranger.” Whatley merely confirms this, the stranger now wearing a British tie, speaking in a borrowed indignation that is both deaf and blind to the truth. The scaffolds on Big Ben are a more apt subject for his pen.

By Raymond Abloh